Danilo Dolci

Danilo Dolci, the Gandhi of Sicily, died on December 30th, aged 73

THERE were few idealists in Italy after Mussolini. The nation and its church were ashamed of themselves. The few Communists with honourable war records were dragged into the mire of Stalinism. Danilo Dolci was different. His theories came from Gandhi, and he attracted from northern Europe the kind of support that Garibaldi had won a century earlier. He sought to improve morality as well as material conditions, and he listened to people instead of drowning them, Italian-style, in rhetoric.

He was big and pale, not really Italian at all. His father was a railway official, and he was brought up by his Slovene mother in Trieste, a city which shared few of Italy's cultural assumptions. He qualified as an architect for the indispensable honorific dottore, then joined a community near Rome that tried to live by Christ's (rather than Christianity's) rules. It failed, and Mr Dolci moved on with his ideals to the squalid fishing village of Trappeto in western Sicily. There, in 1952, he started an orphanage, helped by Vicenzina, a fisherman's widow. He married her and they had five children. He moved uphill to nearby Partinico, where he tried to organise landless peasants into co-operatives. He spoke for the deprived—some would say he put words in their mouths—in successful books, and argued that things need not stay the way they were.

In those days (and sometimes now) Italians habitually disowned Sicily, describing it and its people as African, not European. Successive invaders—corsairs, Saracens, Normans, Bourbons—had ruled as careless absentees. The scarce resources of water, grazing, jobs and trade were rationed out by strong-arm gangs that called themselves Cosa Nostra (Our Thing), to distinguish them from rulers' or landlords' concerns; as the Mafia they bought influence in politics and the church, and emigrants carried their methods across the Atlantic. Sicily's Mafia became a sottogoverno, the island's unofficial regime. Mussolini, intolerant of rival gangsters, suppressed them. America, before sending its men to invade Sicily in 1943, prudently (at the time) enlisted these hoodlums, so the sottogoverno resumed control.

Grab what you can

Danilo Dolci brought to the crime-ridden landscape the townsman's wide-eyed question: why are things just so? The book he was proudest of is called “Spreco” (Waste). It describes the monstrous inefficiency of Sicilian folk-ways—fishermen blowing their catches (and future catches, too) out of the water with war-surplus hand-grenades; cow-dung, precious fertiliser, burned for fuel, while burnable scrub was neglected. Some of his advice was good, some not so good. Little of either was taken. He advocated direct action, but found few actors to join him. Experience had taught Sicilians not to co-operate, but to grab what they could for themselves.

His first notoriety came in 1956, when he gathered a few unemployed men to mend a public road. The police called it obstruction; his helpers walked away; he lay down on the road and was arrested. Skilfully, he drummed up publicity. Famous lawyers offered to defend him free. Famous writers—Ignazio Silone, Alberto Moravia, Carlo Levi, among others—protested. The Palermo court gave him 50 days in prison.

On his release he began to campaign for a big dam on the Iato river, which roared down in the winter rains and dried up in the nine arid months. Given year-round water, Sicilians could grow early fruit and vegetables. But dams require land and money. Mr Dolci tried to stir up the regional government in Palermo and the national government in Rome, embarrassing them with Gandhi-style hunger-strikes, sit-down protests, non-violent demonstrations—theatrical happenings, eagerly reported in northern Europe. Now and then the state was shamed into producing cash, but the locals were not necessarily pleased to see valleys flooded, gardens and olive trees ruined. Moreover, the contractors were either in the Mafia or served it. Mr Dolci became famous as a Mafia-fighter. The Mafia did not fight back. It shot only those it took seriously, such as Communists and trade-union organisers (usually the same people). Some of the romantic northerners in Mr Dolci's chaotic Centro Studi in Partinico longed for an occasional shot their way.

Danilo Dolci was always short of, and careless of, money, although he was helped out from time to time, especially by English families whose fortunes came from the trade in Marsala, the sweet wine of Sicily. In the United States his proto-Christian idealism was absurdly confused with Communism. The Soviet Union claimed a hero it did not own when, in 1958, it awarded him a Lenin Prize for Peace. By the end of Mr Dolci's life the Christian Democrats, some of whose leaders had taken Mafia money, were defunct. Emigration had eased some of the pressure on rural Sicily, while handouts from Rome and Brussels had educated and enriched its middle class, so the old violent habits came to seem shameful. Mr Dolci did not really lead this slow process, but he was one of its precursors. He died very poor.

| Danilo Dolci | |

|---|---|

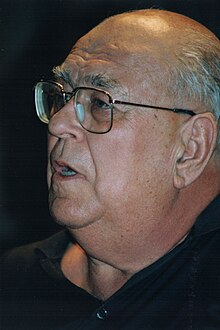

Danilo Dolci in 1992

| |

| Born | 28 June 1924 Sežana, Kingdom of Italy |

| Died | 30 December 1997 (aged 73) Trappeto, Sicily, Italy |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Other names | "Gandhi of Sicily" |

| Occupation | Social activist, sociologist, popular educator and poet |

| Known for | Prominent Antimafia activist and protagonist of the non-violence movement in Italy |

Danilo Dolci (June 28, 1924 – December 30, 1997) was an Italian social activist, sociologist, popular educator and poet. He is best known for his opposition to poverty, social exclusion and the Mafia on Sicily, and is considered to be one of the protagonists of the non-violence movement in Italy. He became known as the "Gandhi of Sicily".[1]

In the 1950s and 1960s, Dolci published a series of books (notably, in their English translations, To Feed the Hungry, 1955, and Waste, 1960) that stunned the outside world with their emotional force and the detail with which he depicted the desperate conditions of the Sicilian countryside and the power of the Mafia. Dolci became a kind of cult hero in the United States and Northern Europe; he was idolised, in particular by idealistic youngsters, and support committees were formed to raise funds for his projects.[2]

In 1958 he was awarded the Lenin Peace Prize, despite being an explicit non-Communist.[1]He was twice nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize by the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC), which in 1947 received the Nobel Peace Prize along with the British Friends Service Council, now called Quaker Peace and Social Witness, on behalf of all Quakers worldwide.[3] Among those who publicly voiced support for his efforts were Carlo Levi, Erich Fromm, Bertrand Russell, Jean Piaget, Aldous Huxley, Jean-Paul Sartre and Ernst Bloch. In Sicily, Leonardo Sciascia advocated many of his ideas. In the United States his proto-Christian idealism was absurdly confused with Communism. He was also a recipient of the 1989 Jamnalal Bajaj International Award of the Jamnalal Bajaj Foundation of India.[4]

留言

張貼留言